Negretti & Zambra was a scientific instrument maker formed in 1850 and they went on to win the only prize medal for meteorological instruments at The Great Exhibition of 1851.

Enrico Angelo Ludovici Negretti (Henry Negretti) and Joseph Warren Zambra were both Italians from the area around Lake Como, a region of northern Italy that was to see high levels of emigration to the UK during the last quarter of the 18th Century, bringing with them their meteorological instrument making skills with them.

Fig.1 Lake Como

Their influence on the design of English weather instruments began with their wheel barometer designs which became a British staple from 1780 onwards. Nearly all early examples will have names such as Gatty, Cetti, Casartelli, Aiano, Polti, Ronchetti, Somalvico & Tagliabue all of whom produced a range of instruments. Such was their influence that, if they did not, then they are likely to have been Italian made and sold to a retailer with an alternative name engraved.

For those Italians who made London their home, the Holborn area was their choice as property was cheap enough to live and the area had an established reputation for instrument making. In addition, the nearby Hatton Garden eventually became a centre for instrument makers and was also where the first Negretti & Zambra premises was situated. Family ties remained strong with Italy and also with other immigrants who moved further afield to the regional centres of the UK and an industry was built around specialist scientific/metrological instrument parts and selling them to larger London or regional makers for finishing, an early example of division of labour that gained much popularity throughout the Nineteenth Century. This is occasionally evident from signatures and markings. (Note the Tarelli of Northampton marked clock wheel barometer which I have in stock that bears a penned note to Mr Tagliabue in the inner door.)

The early Nineteenth Century expansion of the railway and ease of travel in Britain allowed the London retailers opportunity to employ regional agents (or hawkers as they were then derisively called by the local competition) to attempt to obtain wider business opportunities outside of their physical bases. It was one of these agent roles that was first taken up by Joseph Cesare Zambra, the Father of the Joseph Warren Zambra under the employment of the then prosperous Cetti family of London. Born in 1796, Zambra was originally engaged in the building trade prior to his arrival in the UK in 1816 and it is likely that his emigration was facilitated by family bonds already existent with the Cetti family in Italy. Zambra’s new role required him to cover the Eastern regions outside of London and five years later he is stated as marrying Phillis Warren, a farmer’s daughter from the area around Saffron Walden in Essex. It was here that Joseph Cesare Zambra settled and started his own regional instrument making firm and a year later in 1822, the place where Joseph Warren Zambra was born.

The Negretti family’s arrival in the UK preceded the Zambra’s. The surname can be found on barometers dating back to the Late Eighteenth Century and during this early period, they were largely based in the West Country in regional centres such as Plymouth and Bristol. Henry Negretti was born four years before his business partner in 1818 in Lake Como and subsequently moved to the UK with his family in 1830. The young Henry was soon apprenticed to Angelo Tagliabue, a member of another established and successful Italian family. Louis Casella, another talented instrument maker and close competitor of the Negretti & Zambra business was also apprenticed at a similar time and was eventually the successor to Tagliabue’s business. These close relationships will also become more evident later.

Based at 17 Leather Lane in London, Tagliabue’s premises seem to have been turned over or rented out to the Pizzi family by the turn of the 1840’s and Negretti worked for Valentino Pizzi and then Jane Pizzi following her husband’s death in 1841. By this time, Negretti was an adept glass blower and through his technical abilities, went on to form a partnership with Pizzi which was renamed to Pizzi & Co. It is unclear how this partnership ended but by 1845, the company of Negretti & Co was formed and Henry Negretti continued to run this business until the formation of Negretti & Zambra five years later.

Fig 2. – Early Engraving of Leather Lane, London

Fig 3. – Leather Lane today (Little remains of the right hand side but the building to the left remains)

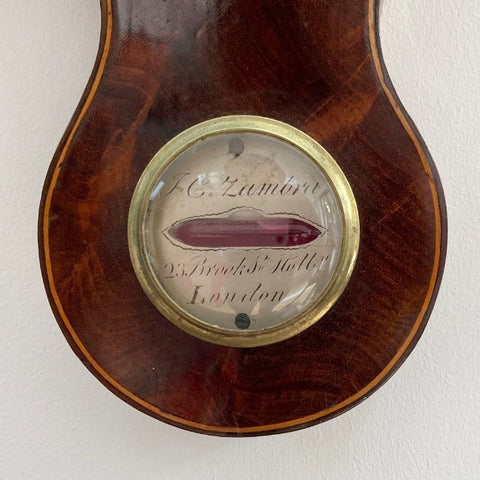

Zambra, who had presumably trained under his Father in Saffron Walden moved with his family to London in 1840 when he was eighteen. Their premises were listed at 23 Brooke Street which was also inhabited by a Joseph Pini. This situation may be the reason that the young Zambra sought a partnership outside of the family with John Tagliabue at 11 Brooke Street.

Figure 4a & 4b – Early Victorian Wheel Barometer by Joseph Cesare Zambra at 23 Brook St.

Amongst the vast array of individuals involved up to this point, you may have noticed that the name of Tagliabue is now a common surname associated with both Henry Negretti and Joseph Warren Zambra and it is clear that the pair would have known of each other’s existence by 1843 when Zambra formed his partnership with the family. Both had also attended The London Mechanics Institute (now Birkbeck College) around this time, an institution founded in 1823 to teach working men science & technology.

Apart from the obvious personal relationships that the future partners had in common with one another, the exact reason why Henry Negretti formed a partnership with Zambra remains unclear. Zambra has generally been considered, at least in the early stages, of slightly lesser status and this seems to be borne out by the representation on their very early instruments where the company name is presented as, H. Negretti & Zambra, which is probably a hangover from the previous company name of H. Negretti & Co. Whether Zambra brought funding to Negretti’s already well established business is unlikely to be understood fully, he was however known to have been a trained glass blower so the pair had a common and essential skill for the creation of meteorological instruments and on the 23rd of April 1850, the fledgling company of Negretti & Zambra was formed with new premises at 11 Hatton Garden.

Figure 5 – Henry Angelo Ludovici Negretti

Figure 6 – Joseph Warren Zambra

It can only be presumed that Negretti’s earlier business provided a very solid and already successful grounding for this new company and their first year of trading must have involved much preparation for their exhibition stand at the Crystal Palace which would run from the 1st of May to the 15th of October 1851.

The company occupied Stand 106A and were entered into Class X, described in the official catalogue as “Philosophical, Musical, Horological & Surgical Instruments” and beside them were numerous recognisable and distinguished makers of the period such as Dollond, Newton & son, Andrew Ross, Smith & Beck, CW Dixey & Powell & Lealand. Their focus was unsurprisingly centred on meteorological instruments and the catalogue states that numerous products such as, Standard Open Cistern Barometers, Self-Registering Barometers, Pocket Sympiesometers, Sixes Self-Registering thermometers, Hygrometers and Pressure Gauges could be found at their stand. For their efforts, the company would eventually be awarded the only prize for meteorological instruments at The Exhibition, no mean feat given the amount of instrument makers noted in the Exhibition catalogue.

The hard work and effort also paid further dividends for the partnership when soon after The Exhibition they were bestowed with a Royal Appointment from Queen Victoria for the production of meteorological instruments. The receipt of an Exhibition Prize Medal and a Royal Appointment in a company’s first year of business was an astonishing achievement and the effect on the company’s growth thereafter was equally positive.

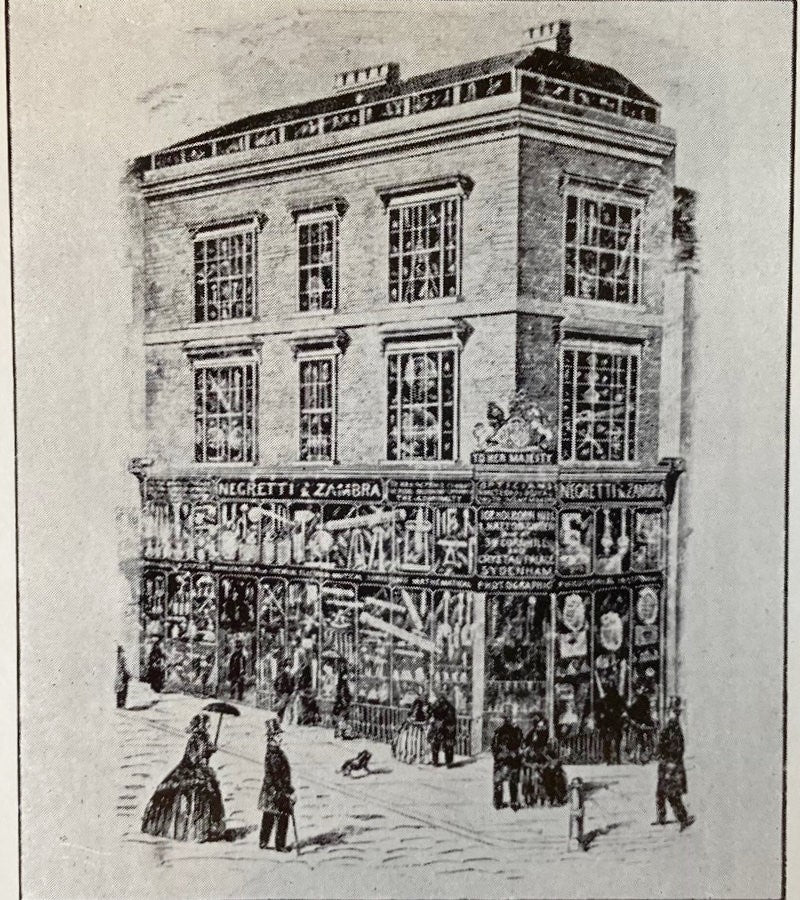

Figure 7 – An example of the Great Exhibition Prize Medal

The 1850’s were a prolific period for Negretti & Zambra, their cash books from the first half of the decade show that they were now supplying many of the older and more established Italian émigré London businesses such as Tagliabue, Pini, Ronchetti, Pastorelli and even the Casella business which had been formed following the death of Angelo Tagliabue (Negretti & Casella’s former master) in 1844. It is also notable how many established English businesses they were supplying, many of which were co-exhibitors at the Exhibition such as Smith & Beck, Horn & Thornwaite & Carpenter & Westley. Regional businesses such as JB Dancer, Abraham, Chadburn, Gardner & J Davis & Son were also trade customers. The image below shows an engraving of the early Negretti premises at 11 Hatton Garden proudly showing the Royal Appointment at the door and if it’s not artistic licence, the amount of product on display was almost incomprehensible!

Figure 8 – Negretti & Zambra’s premises at 11 Hatton Garden.

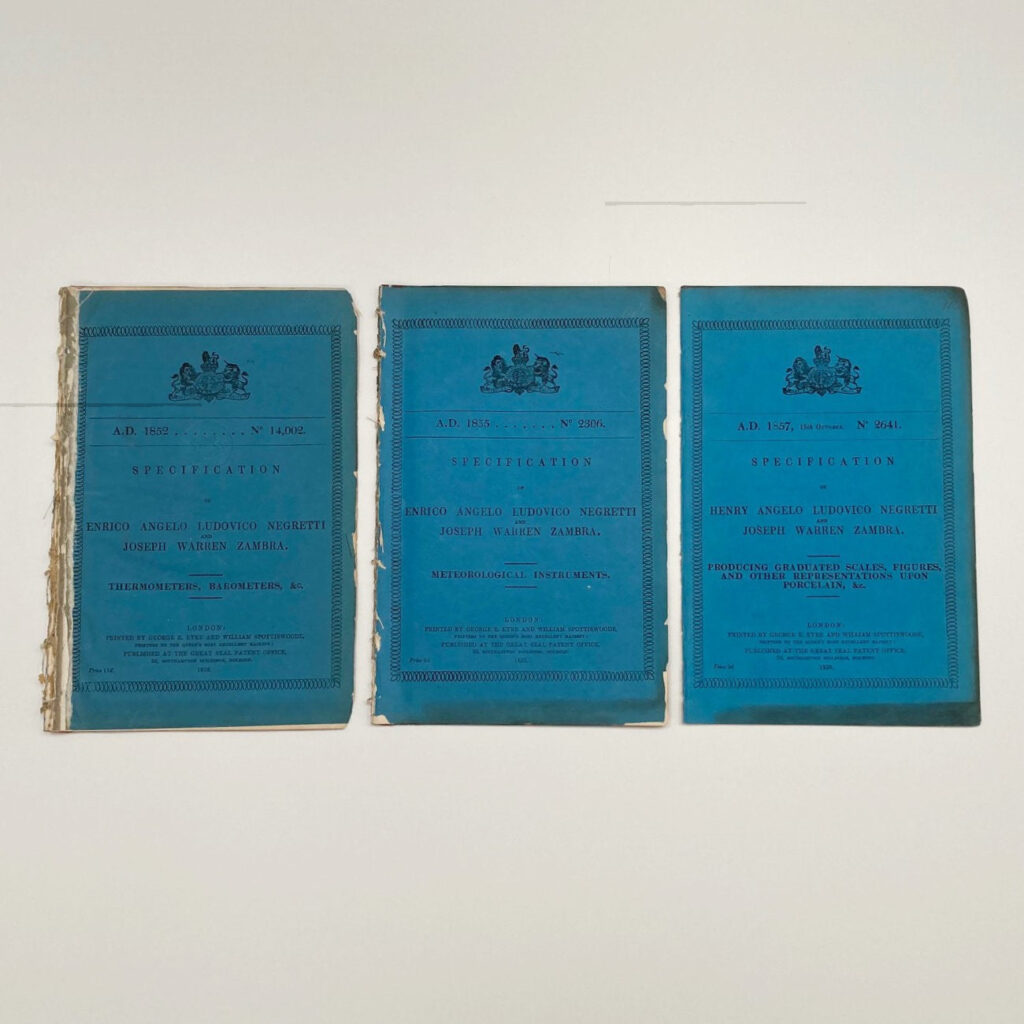

Customers also included The Royal Observatory at Kew, The British Meteorological Society and numerous Governmental and Military Departments and it is likely that many of the patents and new inventions conceived during this early period were at least in part created through collaborations based upon specific requirements, a custom that dates back to the earliest era of scientific instrument making. Owing to the partner’s glass blowing skills, thermometers were an immediate speciality of the company and during the 1850’s they patented numerous self-registering examples for specific uses such as mining, marine and for solar observations. The Patent Maximum thermometer was given special mention in the Report of the Astronomer Royal in 1852:

“We have for several years been very much troubled by the failures of the Maximum Self-registering Thermometer. A construction invented by Negretti & Zambra appears likely to evade this difficulty, the specimens of this instrument we have tried answer very well”

In relation to this particular thermometer, the company also gained an “Honourable Mention” for the invention at the 1855 Paris Exhibition. Although not present, the thermometer was amongst a number of instruments displayed by The Kew Observatory at the event.

Perhaps the simplest yet most recognisable invention was of the application of white enamel to the backs of thermometers. This seemingly obvious development allowed more accurate measurement of the mercurial line and also enabled the development of ever thinner glass bores increasing the sensitivity of the thermometer in general. This invention eventually became the standard for all thermometers beyond that point.

Figure 9 – A selection of original Negretti & Zambra Patents.

By the mid-point of the Decade, the Great Exhibition structure had been relocated from Hyde Park to Sydenham where it stood until it was sadly destroyed by fire in 1936. Negretti and Zambra’s relationship with the Exhibition structure continued and they maintained a showroom at the new location. Having also secured the rights to print images of the original exhibition, the company also set up photographic studios at the new establishment becoming the official photographers for the Crystal Palace Company. Their Carte de Visites became popular with wealthy visitors and the number that can still be found today is testament to the amount of trade this must have generated for the company.

Figure 10 – Negretti & Zambra’s showrooms at Crystal Palace

The latter half of the 1850’s were just as prolific and their work with Admiral Fitzroy paved the way for some of Negretti & Zambra’s most successful and now sought after instruments. Having retired from sea, a career which including the command of HMS Beagle during the historically important voyage with Charles Darwin and a spell as Governor of New Zealand, Fitzroy turned his attention to improvements in Meteorology under The Board of Trade and in 1857 requested the company to provide a design for a stick barometer that would be fit for installation at sea coast stations throughout the UK. He also commissioned the company to construct a double bulb deep sea thermometer which was eventually developed to withstand pressures of up to seven tons below sea.

Fitzroy’s new position at the Meteorological Office and his previous experiences in the Royal Navy had shown him the importance of precise methods of weather prediction for mariners and his intent was to make these expensive instruments accessible to individuals involved in the maritime and coastal industries. The resulting instruments were initially supplied through the Meteorological Office and paid for by the Government but Negretti & Zambra were certainly advertising the early porcelain scaled version to the general public in 1864 as recorded in the company’s, “Treatise on Meteorological Instruments”. Their advertising stated that, “many poor fishing villages and towns have therefore been provided by The Board of Trade, at the public expense, and through the humane effort of Admiral Fitzroy, with first class barometers, each fixed in a conspicuous position, so as to be easily accessible to all who desire to consult it”.

Figure 11 – Admiral Robert Fitzroy

By 1859, Fitzroy had also become involved with the RNLI and the sea coast barometer or the Fitzroy storm barometer as it later became known was provided through Governmental funding and voluntary contributions to RNLI stations throughout the country. These examples are far less common and were provided with distinctive scale plates.

It wasn’t until Fitzroy’s untimely death by suicide in 1865 that Negretti & Zambra started to use the Admiral’s name in conjunction with the barometer, effectively leading to the birth of the Admiral Fitzroy’s Storm Barometer. With the immediate popularity of Fitzroy’s weather predictions and the more widespread availability of the barometer in general, Negretti & Zambra used the name in preference to the old “Sea Coast Barometer” naming convention and although it gained disapproval from Fitzroy’s successor at the Meteorological Office, the company may have felt somewhat entitled to use the opportunity given their close relationship with the man.

In the same period as the development of The Sea Coast barometer was taking place, Patrick Adie was also engaged by The Kew Observatory to develop a new marine stick barometer. The catalyst was a conference in Brussels wherein numerous nations met to discuss a way of producing an accurate instrument for weather measurement at sea. The outcome was a design which was taken up by The Board of Trade as a standard on both land and sea for many years. Admiral Fitzroy was not however, a supporter of this barometer due to the use of metal for the trunk construction. He deemed it too prone to breakage from movement or from gun fire. The latter issue was the catalyst for him developing the gun marine barometer in conjunction with Negretti & Zambra with whom he was already actively engaged. Although it was not quite so widely used as Adie’s design, the marine barometer was evidently a success. A report from Captain Hewlett of The Royal Navy to Admiral Fitzroy reads:

“In the third series of experiments, Mr Negretti being present, five of the new pattern barometers were subjected to the concussion produced by firing a 68 pounder gun with shot and 16lb’s of powder.”

The final year of the decade also coincided with the expiration of Lucien Vidie’s patent for the aneroid barometer. Negretti & Zambra were amongst the first to take advantage of this new freedom and Fitzroy also commissioned them to work on a smaller and more convenient example of this ground breaking instrument. As a result, the company became the first instrument making company to perfect the downsizing of the aneroid barometer for portable use. These early examples are somewhat thicker than the later and more common pocket barometers but the developments made at this early stage created another hugely successful and very marketable product for the company.

Figure 12 – Lucien Vidi – Inventor of the aneroid barometer capsule.

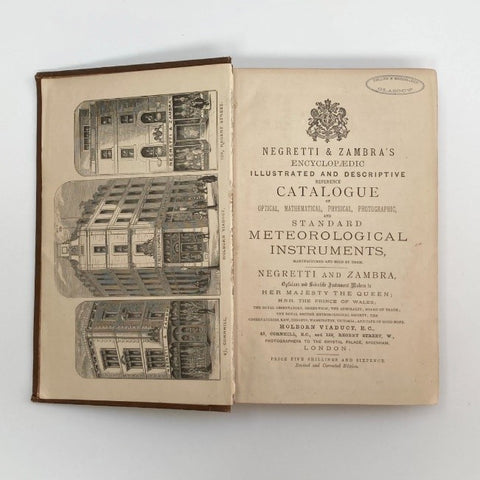

Given all of the developments during this busy decade the company also made the decision to release the first edition of their huge Encyclopaedic Illustrated & Descriptive Catalogue. Its preface gives some indication of the company’s intentions.

“Our endeavour has been to make the work, not merely a list of prices, but in reality a guide for those who are purchasing Scientific Instruments and apparatus generally. All instruments are well described, some more fully than others, depending upon the importance of the apparatus or article under consideration”

From a marketing perspective, the provision of explanatory details relating to their products made everything much more accessible to the general public. This simplification was not only useful to encourage sales, it also provided better general scientific understanding to those who read it. It remains today a hugely useful reference for those interested in instruments of the period and many of its successive volumes remain readily available in facsimile. The originals are somewhat rarer.

Figure 13a & 13b – The front and inside cover of the late 1880’s edition of the catalogue

What is interesting to note is the huge similarity between the catalogues of Negretti & Zambra, Louis Casella and J Hicks. No other studies of the history of these companies seem to have picked up on this comparison but in some cases, the catalogue entries are simply carbon copies of one another. What may first be considered as simple plagiarism by other parties may actually be better explained by the continuation of the close relationships between Anglo Italian families throughout the Nineteenth Century. As we have previously discussed, Louis Casella would have been a close associate of the Henry Negretti given their training under the Tagliabue family. Casella eventually married into the Tagliabue family and ultimately took over his very successful business after his death. Hicks was not of Italian extraction but this equally successful Irishman, was trained under Casella during the 1850’s before finally starting his own business in 1861. How their business relationship was conducted sadly remains unknown at this time, Casella and Hicks may just have been main agents for Negretti & Zambra but it is more likely that they shared ideas and developed instruments in tandem with one another. The rate in which Negretti & Zambra were growing during this period would surely suggest that they required some additional support to produce as many instruments as they did.

Further evidence would need to come to light to understand this symbiotic relationship more fully but we do know from the cash books that Casella was certainly trading with them. The word for word use in some cases of their catalogues would however suggest a much closer association. A very good example of this relationship may be evidenced through the design of the company’s storm barometers of which I have two, one by Negretti & Zambra and another by Hicks. You can see that the pair are almost identical save for the writing at the top of the dome on the scale. The fact that these three companies were perhaps the most successful of their era would suggest that they also very successfully worked together in cornering the market.

Negretti & Zambra – A History (Cont’d)

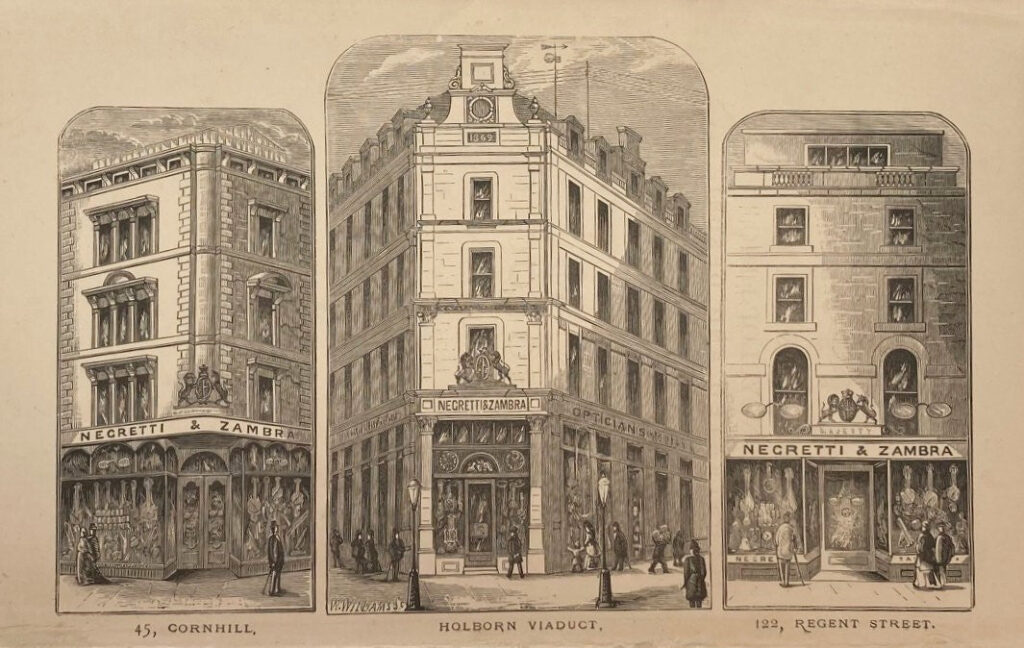

The 1860’s hailed in a vast period of expansion for the company. It first moved from 11 Hatton Garden to larger premises at 1 Hatton Garden after having already acquired additional premises at Cornhill in 1857. Later in the decade, the redevelopment of Holborn and Hatton Garden into what would become Holborn Viaduct demanded a further move to a brand new building at number 38 Holborn Viaduct. The grand opening of the new area in 1869 was attended by their patron, Queen Victoria and their premises were right at the heart of the proceedings. Earlier in 1862 they also purchased the business of the London instrument maker, John Newman whose premises at 122 Regent Street provided the company with a prestigious flagship store in the heart of London. Newman himself was a very well respected maker of meteorological instruments, he provided instruments to Darwin for his voyage on HMS Beagle with Admiral Fitzroy and his famous station barometer was replicated, improved and sold by Negretti & Zambra for many years following his death in 1860, and the subsequent purchase of his business two years later.

Figure 14 – Negretti & Zambra’s London Premises

Figure 14 – A Newman Type Station Barometer by Negretti & Zambra of the 1860’s

The year of the Regent Street opening also coincided with the second large scale exhibition in which Negretti & Zambra took part. Like its predecessor, the 1862 International Exhibition had large purpose built premises for the occasion. Located in South Kensington on a site which is now occupied by The Natural History Museum it opened in May 1862 and housed some thirty thousand exhibitors. Negretti & Zambra’s first entry was allocated to, “Class XIII – Philosophical Instruments & Processes Depending on their Use” and as before, the company was surrounded by some of the finest instrument makers of the period. Names such as Casella, JB Dancer, De Grave Short & Fanner, Elliott Brothers, J Hicks, Pastorelli, Pillischer, Smith Beck & Beck, Breguet, EG Wood & Naudet were all In attendance.

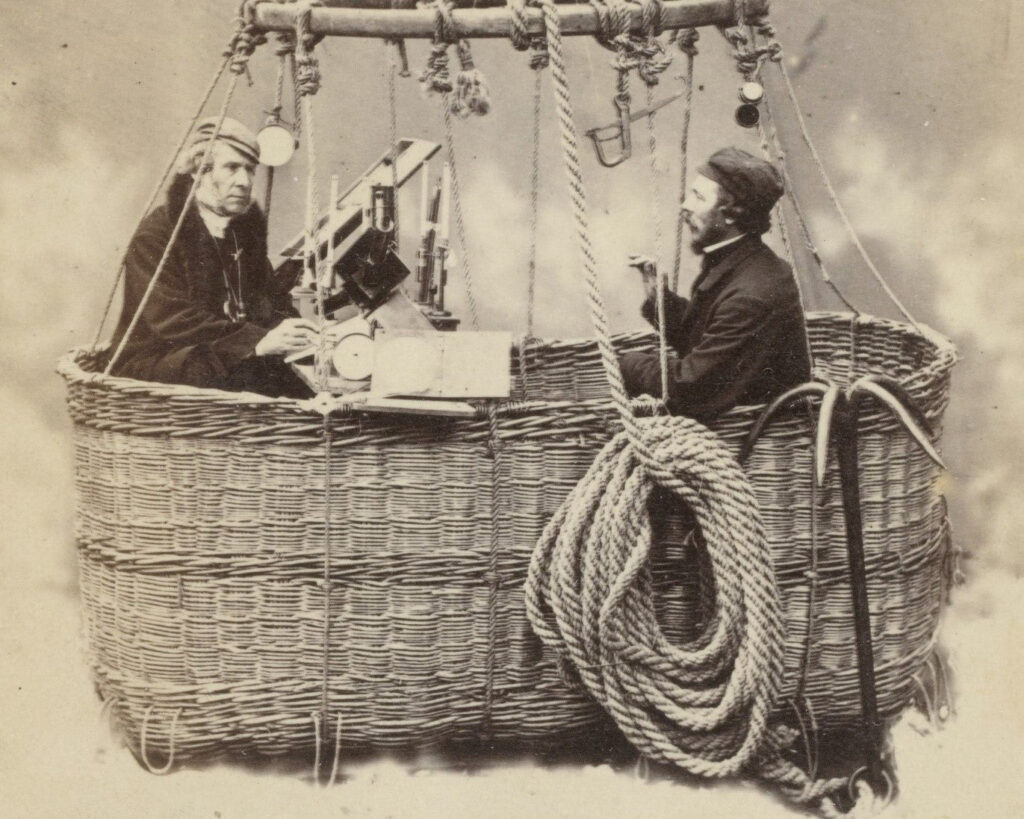

With the rising popularity of photography and Negretti & Zambra’s position at the Crystal Palace it seems obvious that the company would seek to present themselves in regard to this new medium and as such they were also entered into Class XIV – Photography & Photographic Apparatus. During the exhibition, Henry Negretti also undertook experiments with aerial photography conducting a balloon flight in Sydenham to an altitude of 4000 feet with a specially adapted darkroom for use in the air. The daring feat thus proved that aerial photography was indeed possible and I suspect the carefully coordinated timing did much to publicise their attendance at the Exhibition.

Both of their exhibits were successful in achieving a prize medal, the first for “Meteorological instruments. For many important inventions and improvements, together with accuracy and excellence in objects exhibited” and the second for “Beauty and excellence of photographic transparencies and adaption of photography to book illustrations etc.”

Shown below is an example of the 1862 International Exhibition Prize medal awarded to Negretti & Zambra. This example is one which I was lucky enough to purchase and was awarded to the famous scale-makers, De Grave, Short & Fanner who exhibited alongside the company.

Negretti’s interest in ballooning was most likely sparked by the pioneering balloonist and Superintendent of Meteorology at The Royal Observatory, James Glaisher who conducted flights between 1862 and 1866, the memoirs of which were finally published in a book, “Travels in Air”. It is not known whether Glaisher accompanied Negretti on his flight but the company certainly provided aneroid barometers for experimentation purposes. Glaisher later wrote that,

“A third aneroid graduated down to five inches read the same as the mercurial barometer throughout the high ascent to seven miles on September 5th 1862. I have taken this instrument up with me in every subsequent high ascent.”

Figure 15 – James Glaisher & Henry Tracey Coxwell in 1864

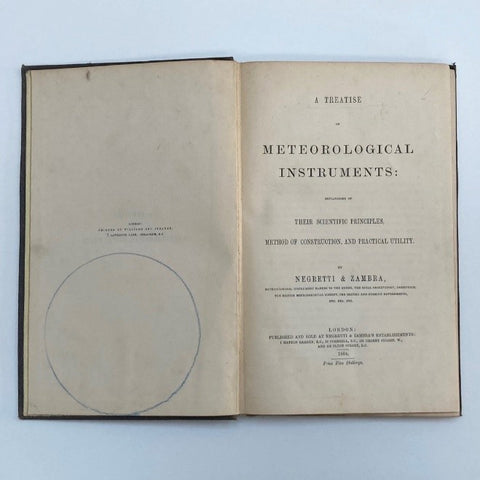

The mid-point of the 1860’s was peppered with disruption for Negretti & Zambra with the building of Holborn Viaduct and their eventual move in the final year of the decade to new premises but the company still found time to complete one of their most influential publications. “The Treatise on Meteorological Instruments”

Figure 16a & 16b – The Treatise on Meteorological Instruments by Negretti & Zambra. 1864

Like its predecessor, the publication was meant to be both catalogue and educational transcript. The instruments displayed within the catalogue are of course those manufactured by the company but they also include thermometers emblazoned with “Casella patent” proving that the company had agreed the rights with Casella to both sell and advertise his instruments. Interestingly, some of the instruments in this publication still also continue to be signed to H. Negretti & Zambra with others simply Negretti & Zambra. A minor point but useful for dating such transitional instruments as they are discovered. What is perhaps more appropriate to this “Treatise” is that its focus specifically on meteorological instruments allowing the company to provide a much deeper and authoritative explanation of the tools associated with the practice of meteorology, a specialism which had been and remained the company’s stronghold for most of its existence. (If you would like to read this book in more detail, please see my book section for details).

The first half of the 1870’s continued to be a period of invention for the company and a further three patents for thermometers were lodged with The Patent Office between 1873 & 1874. The practical uses of the barometer were also keenly considered by the company. A mining barometer was readily advertised and must have been a successful product given the Government guidance provided in 1872 after the discovery that a change in pressure was always recorded prior to a mine explosion. The Mines (Coal) Regulations Act of 1872 stated that, “after dangerous gas has been found in any mine, a barometer and thermometer shall be placed above ground in a conspicuous position near the entrance of the mine.”

Agricultural use for the barometer was also given consideration and a Farmer’s barometer was produced which incorporated a more scientifically accurate hygrometer. Their catalogue states:

“For ascertaining the humidity of the atmosphere, the general character of the weather, and the approach of wind and rain. The Farmer’s barometer combines three distinct instruments – the Barometer, The Thermometer and the Hygrometer, and is equally valuable to the Agriculturist and the Invalid, a difference of 5 to 8 degrees being considered a healthy amount of moisture in the air of dwelling rooms.

Hitherto, the use of scientific instruments of this class has been confined to very few observers, and until lately has borne very little fruit. Nevertheless, through the instrumentality of James Glaisher Esq, FRS, as Secretary of The British Meteorological Society, multitudes of observations have been taken with extreme accuracy, and duly registered; and it is from these carefully collected data that we are enabled in a measure to interpret the various changes that we feel and see going on in our atmosphere.”

The quote is interesting in that it shows the company’s continual development and refinement of the barometer to make it relevant for specific scenarios, the continual efforts to make the reading of the barometer more accessible and also how closely the company were affiliated with the scientific elite. You will remember James Glaisher from his earlier use of Negretti & Zambra aneroid barometers during his pioneering balloon flights and also the deep sea thermometers that Admiral Fitzroy supported. A new and improved double bulb example of the latter was developed and specifically employed during the early 1870’s by The Royal Society’s Challenger Expedition. At that time, it was considered one of the most scientifically fruitful exploratory missions to have taken place for centuries.

The aneroid barometer also saw some developments during this period. The aspiration for self-recording instruments was a function that had already been given close attention by Negretti & Zambra in relation to thermometers during their earlier career and following the development of pocket aneroid barometers, it was perhaps the next and most obvious development was to devise some way for the readings to be recorded without continuous and close attention by the observer.

The company were also responsible for the invention of the “Self-Recording Aneroid Barometer” as it became known. The result was a large cased instrument which included a fusee pendulum clock and a large aneroid barometer. To the centre of the instrument was provided a large brass drum which included a paper graph and a pen. All three elements were closely connected, the clock drove the drum and also regulated the intermittent engagement of the pen to the graph. It also enabled a small tap which was applied to the barometer prior to the pen’s engagement and ensured the barometer was reading correctly. The barometer itself was connected to the pen arm and would regulate the pen movement in line with the pressure reading on the barometer which would then be transferred to the graph.

What I am explaining is of course the first appearance of what we now commonly consider to be the barograph. In more modern instruments the clock was changed and placed within the drum so that it could move under its own power and this enabled the reduction in size to take place. However efficient, the barograph is neither more technically interesting or aesthetically pleasing than these early examples and the catalogues of Negretti & Zambra, Casella, Hicks, JH steward and others all advertised these instruments widely for a period of about ten years. It was of course the development of the barograph that ultimately led to this instruments demise but the latter would never have existed without this very clever piece of engineering.

Figure 17 & 17b – A Negretti & Zambra and a JH Steward Self-Recording Aneroid Barometer.

From 1875 the final half of the decade was largely consumed by the numerous world fairs that continued to be held after the initial success of the 1851 Exhibition. Their catalogue of the 1880’s proudly advertised a prize medal for “Optical & Physical Instruments” from the 1875 Santiago Exhibition in Chile. A year later, three prize medals at The Philadelphia Exhibition for, “Meteorological Instruments, Thermometers and Microscopes” and a further Gold Medal at the 1878 Paris Exhibition for Meteorological Instruments. They did however still find time to lodge two further patents in 1876 for hydrometers and in 1877 for thermometers and hygrometers.

After the huge successes of the preceding thirty years, 1879 was a solemn year for the company. On the 27th of September, the founding partner, Henry Negretti sadly died from acute lung infection. His son HPJ Negretti seems however to have been involved in the company for some time prior to his Father’s death and alongside Joseph Warren Zambra and his son JC Zambra, a new partnership was agreed.

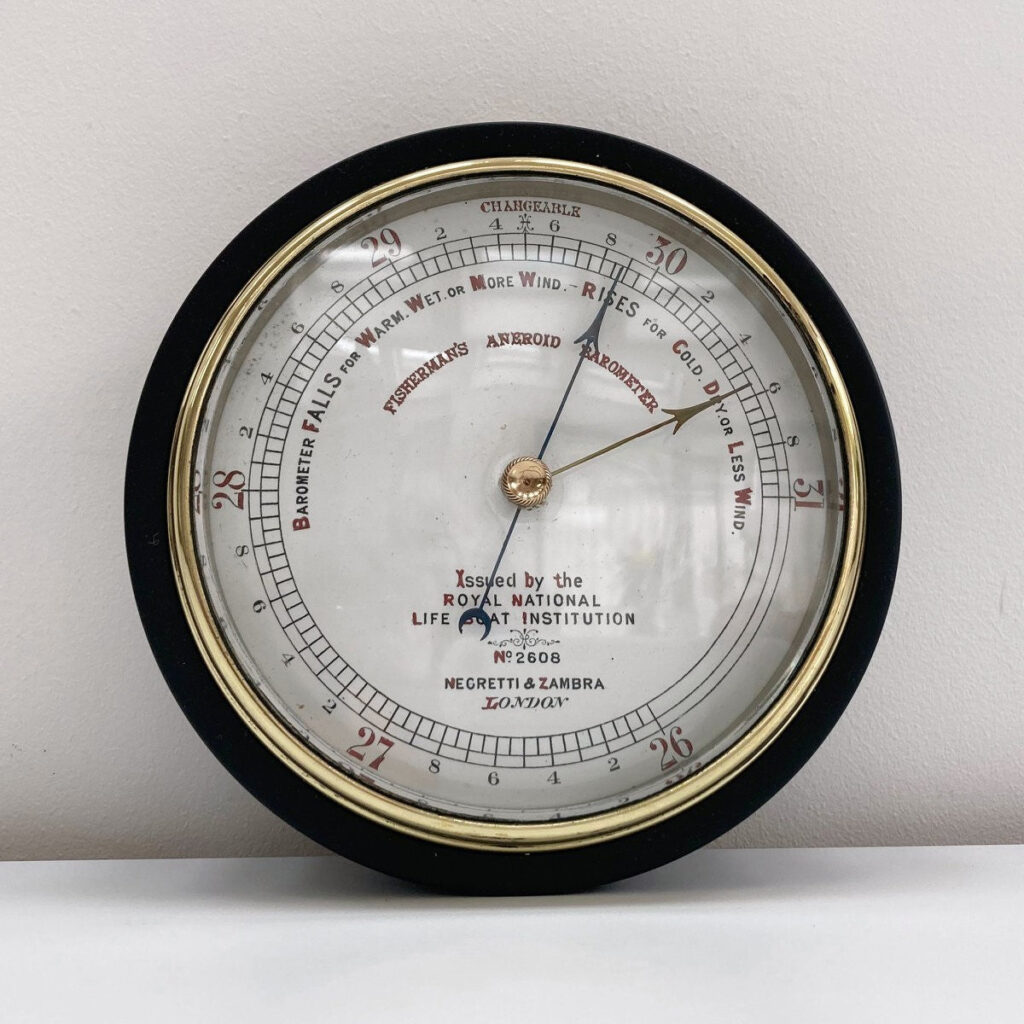

Thankfully, the loss of Henry Negretti did not spell the company’s demise and they continued to enjoy the patronage of the scientific community, Governmental Departments and Royalty alike. The RNLI also continued their affiliation and in the early 1880’s a decision was made to furnish mariners and fishermen with an aneroid barometer that would be suitable for use aboard small vessels and more importantly be affordable to those with a modest income. The reason for this decision was much the same as was intended with the original Storm stick barometer but these small, more portable and much hardier instruments would allow mariners to foretell inclement weather whilst at sea. Both Negretti & Zambra and Dollond were commissioned to manufacture these so called Fisherman’s aneroid barometers and Negretti continued to make them for the RNLI and for general sale for another fifty years or more. The design is simple and yet it resulted in one of the most pleasing and sought after aneroid barometers which are still loved by collectors to this day.

Figure 18 – An RNLI Fisherman’s Aneroid Barometer by Negretti & Zambra

Another similarly aesthetic barometer was also developed during the early part of the decade, the long range glycerine and mercury barometer was intended to allow for more precise reading of atmospheric pressure by using an extended scale. It was described as follows:

“The Long range or open scale barometer consists of a glass tube of the syphon form; one side of the syphon A (or closed end), being about 33.5 inches long, and the other only a few inches in length. To this short end is joined a length of glass tubing B, of a much smaller internal diameter; both tubes are of equal length, the smaller one being open at the top. The large tube A, is filled with quick silver, and the small tube B is partly filled with glycerine, a fluid many times lighter in specific gravity than quicksilver; the rising and falling of the quicksilver column in the large tube having a lighter fluid to balance, and that dispersed over a larger space by reason of the difference in the diameter of the two tubes, a longer range is obtained due to the unequal capacity of the two tubes and the difference in the specific gravity of quick silver and glycerine.

The range of these barometers is from six to ten inches to the inch of an ordinary barometer. A hundredth of an inch can easily be observed without the use of a Vernier. It is a most interesting instrument, as from the extremely extended scale the slightest variation is plainly visible. The actual size and form is about that of an ordinary barometer”.

These examples are rarely encountered so it is likely that they were only produced in small numbers. They are so aesthetically pleasing that they were probably aimed at the domestic market as a means to avoiding the complications of using a Vernier, however I suspect for that reason alone they were not considered serious enough by the more scientific user. It is perhaps one of the few examples where the scientific ingenuity of the company perhaps failed to capture the market by trying to appeal to two different audiences.

Figure 19 example of The Negretti & Zambra Glycerine & Mercury Long Range Barometer

The exhibition calendar remained full for the company during the 1880’s although thankfully more close to home in the main. There were Fisheries Exhibitions in Norwich, Edinburgh and London between 1881 and 1883 for which numerous prize medals were awarded and the International Health Exhibition in 1884 for which the company’s thermometers remained a firm favourite with the judges. The most unusual and farthest reaching of all of their exhibition history was the Java Exhibition in 1883 although a gold medal for their optical instruments was perhaps enough solace for the distances involved.

In 1888, the remaining founder Joseph Warren Zambra retired and his other son MW Zambra joined his brother JC Zambra and HPJ Negretti to create a new partnership, although just four years later JC Zambra died, pre-deceasing his Father by five years. Given the numerous management shifts and final loss of both founding partners it is perhaps forgivable that the 1890’s seemed a rather sparse period for Negretti & Zambra in regards to inventiveness. That is not to suggest that the company were any less successful, a fact made clear by the company’s purchase of property in Islington at Half Moon Crescent in 1901 which was used as a means to consolidate its manufacturing base. The proceeding demolition of the site and the erecting of new buildings would by 1911 eventually become the famous, Half Moon Works which served the company for many years to come.

The company endured the First World War and were employed throughout by the Ministry of Munitions providing instruments for military use. Their involvement with the development of early aviation instruments was also to prove significant for the company’s direction in later years.

To prove that they had not lost its focus on the development of meteorological instruments, perhaps their most popular patent was lodged in 1915 for the company’s new weather forecasting suite of products. Negretti & Zambra had spent most of its history attempting to make weather instruments more accessible to the domestic audience for obvious business reasoning and the new forecasting products which allowed a user to interpret air pressure and wind direction into a reasonably accurate forecast at a moment’s notice was simply ground breaking and effectively demystified the often confusing movements of the barometer needle.

The suite of products ranged from large travel sets including a forecasting aneroid barometer and large desk type forecaster to small pocket aneroid versions and even simple ivorine forecaster discs or standalone desktop versions could be used in conjunction with any pocket or wall aneroid barometer. The range therefore suited every different pocket and was wildly popular in the post war climate when it eventually found its feet. It was perhaps the last of the Negretti & Zambra barometer developments that really broke the mould for the domestic market before the onset of radio weather forecasts and it began to publish its own weather forecasts using the product in its London stores. Examples of these products remain hugely popular with collectors who wish to take a more analogue and hands on approach to weather prediction and appreciate the superb craftsmanship of these weather instruments.

Figures 20 a, b, c, d – Various examples of Negretti & Zambra’s Weather Forecasting products

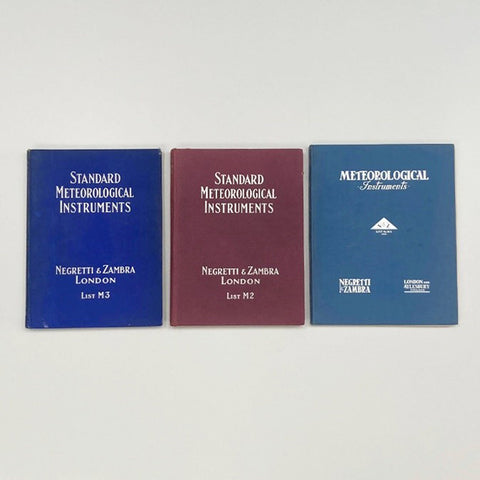

The 1920’s also saw a renewal of the Negretti & Zambra catalogue. The new format had a decidedly different feel to its predecessor which reflects the radical developments in printing and publishing that had taken place in the intervening years. The M2 catalogue of Standard Meteorological Instruments as it first appeared in the 1920’s presented a slimming down of its voluminous Victorian product range. Whether that was purely down to company focus or lack of third party supply in a post war environment is not clear but it does introduce aviation instrumentation and some more industrial type products which clearly show a diversion away from high street retailing. Gone are the informative explanations of yester year so it must be assumed that the company expected their customers to be better informed or of an already scientific leaning.

Further management transition happened during this period, HPJ Negretti died in 1919 and G. Zambra retired two years later in 1921. The firm however still managed to maintain family ownership and HN Negretti, PE Negretti & MW Zambra extended the partnership structure of the founders. MW Zambra finally retired in 1936 leaving the Negretti family in sole charge of the company. The M3 catalogue was also released in the 1930’s in a very similar format and with much the same content.

As is evident from their new catalogues, the First World War brought about a greater leaning of its focus to industry rather than retail. Instruments continued to be made for public consumption but aviation and industrial markets were likely to have been more lucrative. This change was further compounded during the Second World War with the destruction of their Holborn Viaduct premises during Luftwaffe raids in May 1941.

Figure 21 –Aftermath of the Luftwaffe Raid at Holborn Viaduct

The premises were sadly never rebuilt and the company moved its Head Office to the existing premises at 122 Regent Street which had both office space and a retail premises at street level.

The retail premises were not the only Negretti & Zambra buildings to suffer during the war and their Half Moon Works also sustained bomb damage whilst carrying out work for the Government. This event led the company to occupy a safer temporary works in Chesterfield where they were set to work in manufacturing various gauges and thermometers for use in RAF planes. This works did not remain after the war due to the distances involved but an aviation factory was set up in Chobham to continue to service that industry.

The end of the war also saw the death of HN Negretti in 1945 and three years later, the company was incorporated into a Limited Company with the Negretti family maintaining majority ownership. The post war era saw an upturn in Negretti & Zambra’s fortunes and a new manufacturing site was purchased in Stocklake, Aylesbury where a housing estate was also constructed for its employees. Expansion overseas also saw sites crop up in Holland, South Africa, Canada & Australia.

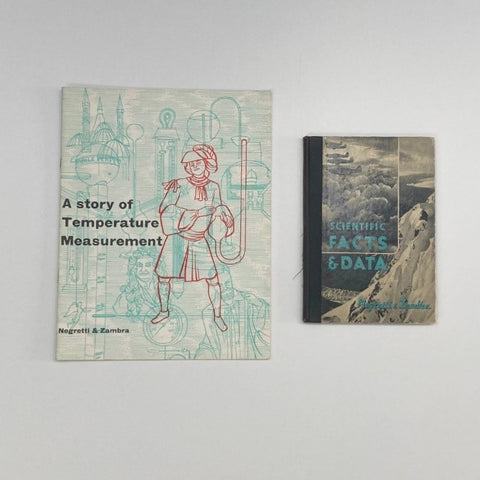

The 1940’s saw the last of the large format catalogues that the company produced and the M4 also displayed a new Negretti & Zambra triangular shaped logo. The catalogue again remains largely the same as its Twentieth Century predecessors but gone are the aviation instruments. This feature is perhaps not surprising given that the company was by this point slowly drifting into two distinct arms of business, one serving aviation which would eventually become Negretti Aviation and the other manufacturing its historic catalogue. The company did however publish a rather unusual small book entitled, “Scientific Facts & Data”. It was unusual in the sense that The United Kingdom had declared war with Germany just two months prior to its publication and also that it is simply a glossary of meteorological terms with associated facts and explanations including such random facts as the temperature of various warm and cold blooded animals. This attempt was perhaps not quite as instructive as their previous attempts.

Figure 22 – The Negretti & Zambra M Series Catalogues

The last formal publication from the company was entitled, “A Story of Temperature Measurement”. It is an informative historical work although it seems to have been published as an interesting aside for customers rather than as a sales generating tool. The book only stretches to twenty pages and provides a good summary for the reader, surprisingly the first mention of their products comes on page eighteen but six of their thermometers are referenced and provide some good insight into the design styles of that period.

The Mid Sixties heralded the company’s almost entire removal from London which had been planned since the creation of the Aylesbury site and the long transition included the re-housing of workers and their families who wished to continue to work for the firm. The Half Moon works was closed and demolished and the flagship premises at 122 Regent Street closed its doors for the final time in 1965. A smaller retail outlet was opened at 15 New Bond Street and an opticians business at 15C Clifford Street but it is not clear how long these premises remained operational beyond that point. The instrument business for which this article is mainly concerned really ceased to exist by 1980 when this part of the company was sold off to the British Rototherm Company and the Negretti family finally ceased its long association with the company at this point.

The Negretti & Zambra Group thereafter continued to supply industry and aviation but continued on a slow process of decline thereafter. The business was sold off to Meggitt PLC and the name was changed to Meggitt Aviation in 1993 and the remaining automation arm of the business was sold off and finally succumbed to failure in the year 2000. A rather ignominious end to this most famous instrument making company.

It could be said that the change in focus to industry was the correct move in the unsteady and changing environment of the early Twentieth Century but it ultimately led to their final demise. We will never know whether changing tastes of retail consumers would also have promoted the same conclusion in the Post War environment however what remains of the company’s Victorian and Early Twentieth Century heyday are some of the finest and accurate instruments from that period and continue to provide pleasure to collectors across the globe.